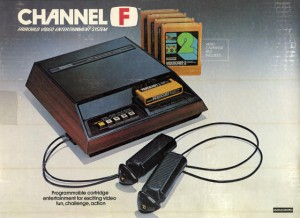

Die Geschichte der Game Cartridge? Bis heute hat das anscheinend niemanden so recht interessiert. Die Geschichte der Game Cartridge wurde bis heute nie aufgearbeitet, dabei ist die Erfindung der Game Cartridge mehr als ein Meilenstein in der Geschichte der Videogames gewesen: ein Wendepunkt, das erste stabile Wechselmedium, welches das sofortige Austauschen und Spielen von unterschiedlichen Spielen auf einem Gerät erlaubte. Benj Edwards beschreibt die historische Erfindung der Cartridge in einem langen gut recherchierten Artikel im Business Magazin Fast Company. Die zähe und strapazierfähige kleine Plastikbox war ein grosser technischer Durchbruch in den 1970er Jahren. Erfunden wurde die Box von einer heute vergessenen Firma und von zwei Leuten, die nie eine Anerkennung für ihre innovative Tat erhielten. Die Firma Fairchild hatte damals sogar eine eigene Spielkonsole entwickelt und sie zusammen mit den allerersten Cartridges unter dem Namen Channel F auf den Markt gebracht.

Die Geschichte der Game Cartridge? Bis heute hat das anscheinend niemanden so recht interessiert. Die Geschichte der Game Cartridge wurde bis heute nie aufgearbeitet, dabei ist die Erfindung der Game Cartridge mehr als ein Meilenstein in der Geschichte der Videogames gewesen: ein Wendepunkt, das erste stabile Wechselmedium, welches das sofortige Austauschen und Spielen von unterschiedlichen Spielen auf einem Gerät erlaubte. Benj Edwards beschreibt die historische Erfindung der Cartridge in einem langen gut recherchierten Artikel im Business Magazin Fast Company. Die zähe und strapazierfähige kleine Plastikbox war ein grosser technischer Durchbruch in den 1970er Jahren. Erfunden wurde die Box von einer heute vergessenen Firma und von zwei Leuten, die nie eine Anerkennung für ihre innovative Tat erhielten. Die Firma Fairchild hatte damals sogar eine eigene Spielkonsole entwickelt und sie zusammen mit den allerersten Cartridges unter dem Namen Channel F auf den Markt gebracht.

„Consider the humble video game cartridge. It’s a small, durable plastic box that imparts the most immediate, user-friendly software experience ever created. Just plug it in, and you’re playing a game in seconds.

„At the time, memory was very, very expensive,“ recalls Haskel. „I mean, a penny a bit, or something like that.“ That limited both the graphical capability of the system and the complexity of the software. Each game had to be less than two kilobits (or 256 bytes) in size. For comparison, this paragraph of text alone takes about 384 bytes to store electronically in its simplest form. […]

Typically, once an EPROM was programmed, a hardware designer would either solder the chip directly to a printed circuit board or insert it into a delicate socket soldered onto such a board. It became obvious to Kirschner almost immediately that if consumers were going to use their console, they needed a way to change out those ROMs in a user-friendly fashion. So Alpex’s engineers decided to mount the fragile ROM chip to a circuit board and, in turn, connect the chip’s pins to a more durable connector that could withstand repeated insertion and removal.

That’s how the first prototype video game cartridge was born.

„We went to RadioShack and bought these little plastic boxes,“ recalls Kirschner. „And we were able to plug the little box into the console with a connector we put on it.“ Kirschner remembers RAVEN’s cartridge enclosures as being about five inches wide by three inches high by a couple of inches deep. Each black plastic box encased a circuit board with a memory chip containing video game code mounted on it.

These memory modules interfaced with the RAVEN console via a 25-pin connector protruding from the wide dimension of the cartridge box. Such a connector could withstand far more insertions than a delicate memory socket, but its 25 small pins were not suitable for consumer use. Alpex punted that problem down the road, setting the stage for a second round of video game cartridge innovation that took place at an entirely different company.

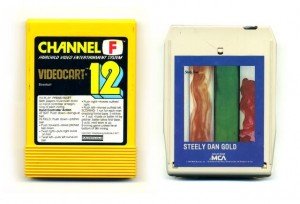

[…] zeroed in immediately on the familiar form of the 8-track tape cartridge, an audio recording format which gained significant traction in the 1970s through its use in car audio systems. Relatively rugged, easy to insert and remove with one hand, and vibration-resistant, the 8-track tape proliferated where the comparatively delicate vinyl record feared to tread. He chose a shape and size for his new game cartridge enclosure that closely matched the 8-track tape standard. Then he added ribbing around the edges for improved grip, and selected a bright yellow plastic color to make a statement. Cartridges were the true star of the show, he figured, so they deserved to stand out. […]

Each game package also came prominently numbered, starting with Videocart-1. This provided an easy way to refer to cartridges which contained multiple games of varying genres (Fairchild ultimately made it up to Videocart-26). In retrospect, the numbering system reflects a time when no one had any idea how many cartridges were enough for a system, how long a system like the Channel F could last on the market, or about the later appearance of third-party game publishers which could quickly balloon the number of games available into the hundreds, if not thousands. (Anyone up for a game of Videocart-963?) […]

The Channel F made its first public appearance in June of 1976 at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago. However, the company only displayed a non-working empty shell, so the system did not attract much press attention. A few weeks later, the Channel F made a much bigger debut nationwide as part of a July 6, 1976 article in Businessweek called „The Smart Machine Revolution.“ The multi-page feature touted the Channel F alongside cars, watches, and scales as a product that demonstrated the enormous potential of microprocessors in everyday consumer products. […]

Ultimately, the games-as-software model allowed the possibility of selling a base console on a slim margin (or even a loss) to achieve as high a market penetration as possible, then making up the loss from sizable profits of relatively inexpensive-to-duplicate software. This same business model is what drives the video game industry today, almost 40 years later.

// Article by Benj Edwards, tech history journalist, in Fast Company Magazine, January 22, 2015 //

http://www.fastcompany.com/3040889/the-untold-story-of-the-invention-of-the-game-cartridge